The way you say something—does it matter? I mean, is there a difference between, for example, “take on a supine position,” and “take a rest on your back?”

- Does it matter how you say something?

- The way you say something—does it matter?

Yes or no? When? To what extend? And why?

When teaching movement lessons, Yoga, or animal movement, or physical therapy, or somatic education… whenever you give movement instructions, is there any significance regarding how you phrase sentences? Is it important or not? Does it have consequences, does the way you voice your intention influence the movements and learning of your students?

- “… is there any significance in how you phrase sentences?”

- “… is there any significance to how you phrase sentences?”

As a teacher of somatic education, or to some extend even as a certified FELDENKRAIS® teacher, if you will, I ask questions—rather than hose you down with rules and regulations.

This is unusual, and might sound a bit odd in today’s world. Especially considering that most GCFP® “Guild Certified Feldenkrais Teachers” were as eager as anyone to follow the even most non-sensical and most damaging pandemic rules and regulations since April 2020, to the point, and beyond. Like a slightly moist sponge is ready to soak up water they were ready to soak up whatever guideline, ruling or regulation was thrown at them. And they condemned everyone who did not. How long has this been going on?? Doesn’t this turn the main purpose of The Feldenkrais Method—as intended by Moshé Feldenkrais—upside down?

But I’m getting off topic. Let me start again:

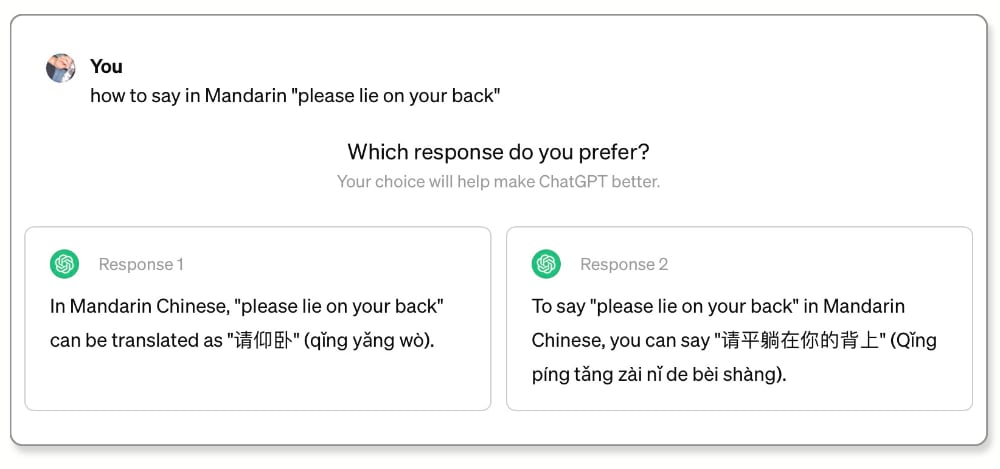

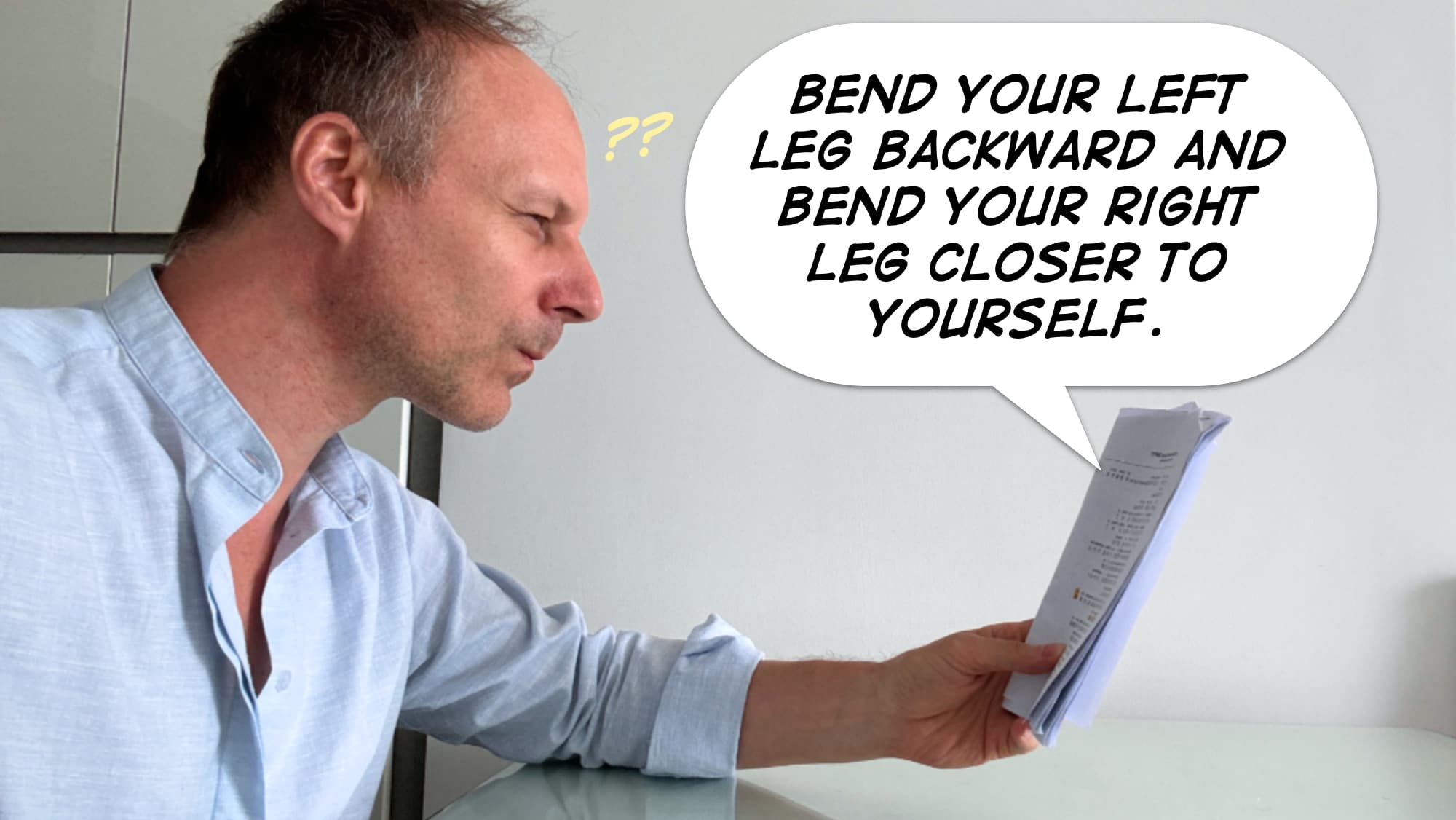

I was reviewing some of my videos, when I stumbled upon an online teaching session I gave a few years ago, to Chinese students in China. Everything I said was translated into Mandarin Chinese by a translator. Here’s a screenshot for your visual entertainment (I blurred out the students for privacy):

My first instruction in this lesson was “Please lie down on your back,” which the translator translated to 请仰卧 (qǐng yǎng wò), rather concisely. 请 (qǐng) meaning “Please” and 仰卧 (yǎng wò) being the noun phrase of interest, meaning “lie down in supine position.”

Now, as a Non-Chinese speaker I can’t write about linguistic aspects of Mandarin Chinese. But I can fool around a bit (or make a fool of myself, more likely). Let’s break down the individual words of this short sentence, via a bullet list:

- 请 (qǐng) means “please”

- 仰 (yǎng) means “to face upwards”

- 卧 (wò) means “to lie down”

And, of course, the last two words are glued together, which is called a “noun phrase” in grammar speak, and thus becomes “仰卧” (yǎng wò).

Easy enough.

And where’s my beef? The beef I have with this, as a teacher of somatic education, is that “Lie down in a supine position”… I mean… let me phrase this as a question. What do you reckon is the difference between saying:

- “Please lie down in a supine position.” and

- “Please come to rest on your back.” ?

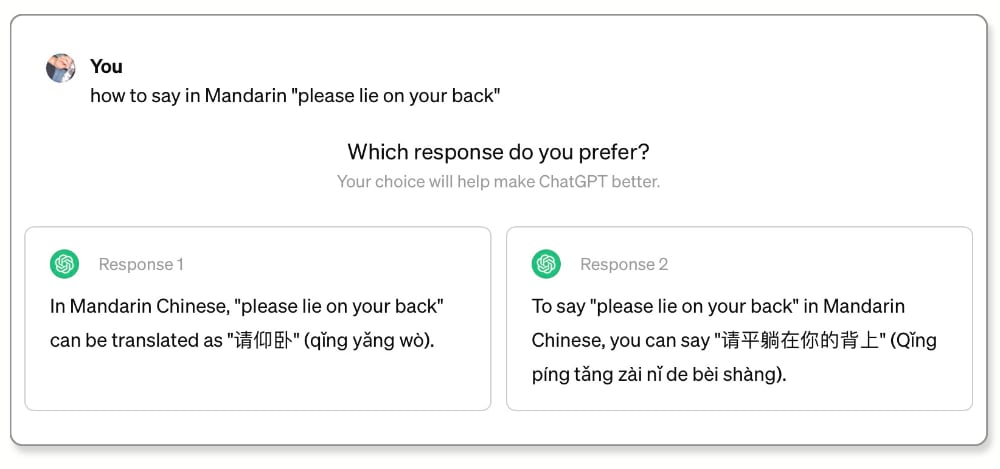

I want to end this post with sharing my personal point of view. If I were to teach a class in Mandarin Chinese myself, I would go with the longer phrase “请平躺在你的背上。(Qǐng píng tǎng zài nǐ de bèi shàng.)” Meaning, “Please lie down on your back.” For three reasons:

1. “Supine position” is a complete concept, like a ready made meal. However, I want students to cook for themselves, to put things together starting from raw ingredients. “Do this, this, and this, and see what it is, and how it tastes like.” Metaphorically speaking.

2. By addressing everyone with the singular “you” 你 (nǐ) rather than the plural “you” 你们 (nǐmen), I can make it sound like as if I’m talking to every person in the room personally, directly, even if there’s 60 people in the room. In my mind lessons of somatic education (as intended by Moshé Feldenkrais) are a personal experience, and are to foster personal learning; and certainly not to turn the movements of individuals into a group choreography, or critical thinking into the lockstep of an indoctrinated hive mind.

- Please rest on your backs.

- Please rest on your back.

3. Furthermore, this phrase includes a tactile cue, “your back.” I might double down on that with another sentence, “Sense how you rest on the floor.” Therefore, the instruction “Please lie down on your back” served as a preparation, a lead-up to the next sentence, in the congruent, continuous flow and progression that is the lesson.

Oh, one last thought: my last paragraph reminds me of the song, The Moldau, by Bedřich Smetana. Like a movement-based lesson in the original spirit of Moshé Feldenkrais, the song starts out by telling the story of a small, gentle, light little water running down the mountains of the Bohemian Forest, which then flows through rural Czechoslovakia, and finally becomes this beautiful, majestic, big river, as it reaches Prague. Home.